Heather Allen’s New Figuration

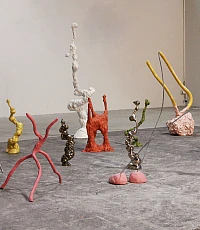

In recent years Heather Allen has been making strange, dubious sculptures, puzzling creations that lend one’s fantasy wings and hijack the viewer into worlds difficult to enter. They will surprise, perhaps shock, certainly confuse him or her because:

Up till now, the English artist has been known for her installation-based works. Their didactic impulse was directed at social and socio-political themes such as freedom and breaking through barriers, presented in model-like settings. The human figure was the core and centre of this artistic endeavour: people as part of expanded architectural and social space.

And now this!

Weird, organic entities occupy the exhibition space as solitary, three-dimensional objects which remain silent. Most of them quietly shine in their restrained, languorous colouring, growing out of the floor as if by magic. They remind one of an excursion to a natural history museum, an archaeological and paleontological collection, a trophy room and salons, cabinets of wonders of quirky amateurs.

Has someone crossed coral seeds with the sperm of the last mammoth here?

We have, however, no explanation to clarify things, the artist herself speaks only of ‘form’ – aha! – so it’s about abstraction.

With her new sculptures, Heather Allen makes the immediate sensory event into a mediating medium of non-verbal knowledge, the sensory experience into the foundation of knowledge and understanding.

These are big claims for sculptures that initially appear modest, and forego all monumentality. Rather, some of these creatures find themselves on different planks, swaying over an abyss of comedy and seriousness. An artist who manages this with such aplomb as Heather Allen must have been blessed with a fathomless sense of humour, and must, therefore, be English.

Perhaps she’s seen at some time the illustrations of tower-like piles of worm excrement made in wood from photographs that the famous Charles Darwin commissioned for his script, ‘The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms’. In any case, I thought I could hear the distant curses and smirking of Shakespearean witches as I stood alone with the sculptures – and finally raucous laughter from the region of Monty Python.

However, it would be too easy to reduce Allen’s sculptures to aspects of the comical or random because of their unusual, figurative forms. Even there, where shining, erect members unfold their glory like hyper-sexually loaded dildos and embarrassingly dazzle the viewer, we are dealing with the results of a goal-oriented strategy and a conceptual process.

What looks as if it emerges from a continuous process of growth is the result of planning, development and correction. Sketches, drawings and other drafts are stepping stones and mark the course to compelling sculpture. In fact, these new figurations are based on two-dimensional research, which accompanies the development of the sculpture to its final fixing as a ‘form’ in space.

The raison d’être of these sculptures is their figuratively formed existence; they justify themselves by their manifestation.

Heather Allen’s ‘forms’ are singular, unique artworks that have not been seen before in such quality. Perhaps Louise Bourgeois and Alberto Giacometti are waving from their distant, massive clouds -, but in the circle of contemporary living artists, I have not found anything comparable.

Heather Allen’s art points us in another, a new way: and that is how it should be!

Dirk van der Meulen, honorary Professor, UDK, Berlin, November 2015

Alien Residents, 2011

Big Themes on a small Scale

English sculptor Heather Allen has been making small figurative sculptures for several years, which she sees as self-portraits. At first, the rather hand-sized figures were all female, then she added male versions of herself, either clothed or naked. There are now several hundred of them, many in private collections. In a sense, the figures are individuals – with their own postures, gestures and facial expressions. For exhibitions, the artist arranges them in site-specific groups. Some figures stand alone, others are related to each other or look at the viewer. The compositions are interspersed with clues and stories that invite the viewer to decipher them for themselves.

These curious self-portraits have so far consisted mainly of an oven-hardening PVC modelling paste (Sculpey) that can be coloured to define details such as eyes, lips, pubic hair and nipples. Since the summer of 2008, the artist has been working with a new material: black moulding wax, which is also used in bronze casting. Unlike the Sculpey figures, they are not coloured. They are almost identical to the material and remain largely anonymous. For Heather Allen, these black figures are a raw, archaic image of herself, manifesting like a horde of prehistoric humans. Their physical, sometimes threatening presence dominates, while the coloured figures have a stronger psychological or intellectual dimension for the artist.

Another innovation in her work is the combination of her figures with built structures. Previously, she placed the figures exclusively on pedestals or in pre-existing situations – almost a hundred surrogates populated Sigmund Freud’s couch, desk and chair (At Home with Freud, 2002), or occupied a basement inventory installed in a gallery like small, hidden, resident ghosts (Basement, 2001) – but now they interact with ladders and vertical architecture, which the artist also sees as autonomous sculptures. The scale of the figures plays a crucial role. In a sense, the viewer sees the sculptures through the eyes of the creatures, which are between 15 and 18 centimetres tall.

Heather Allen’s series of miniature works began with a 1998 video in which the artist animated a moving figure using traditional stop-motion techniques. The story it tells is as simple as it is profound: Heather Allen’s alter ego wakes up in her creator’s apartment and climbs over the huge furniture to reach a window, which she struggles to open. Then she jumps out. Into freedom? Into death? The ending remains open.

The narrative, deeply rooted in psychology, is a defining feature of Heather Allen’s work. In the towers and ladders leading upwards, the motif of the quest for knowledge is evident, but it raises more questions than it answers. Through the figures, Heather Allen explores the poetic absurdity of states of life that challenge the viewer’s imagination in the form of transitive moments. The artist is primarily concerned with such movements of the mind. In this way, very large themes can be unexpectedly evoked on a small scale.

The “Inverted Harem”

Heather Allen’s world is like an “inverted harem”. The women are by themselves. As the prince is constantly away on his travels and the eunuchs have long since died out as strict guards of the harem, the women have decided to attend to their own affairs. The prince has a strong preference: the women all look the same. They all have a 1950’s “Mary Long” hairstyle (but that dates back as far aas the pre-war period). Their bodies are not slim, but nor are they plump. They are, it could be said, stocky, and have a natural but not explicit eroticism.What distinguishes the women, who are either naked or are wearing identical tight-fitting tracksuits, is their facial expression and body language.

Heather Allen’s women are around 15 cm tall and made from modelling clay. As they all look the same, the difference between them is even more focused on the facial expressions and gestures. This is one aspect that makes them special. The other key element – which primarily becomes visible in pieces with groups of women – is the communicative interaction they are involved in.At first sight the women are simply standing, sitting or lying around. It is only upon closer examination that the intensive group interaction between them becomes apparent. They cooperate. They are of the same and different opinions. They wander off and find their way back.

Heather Allen pulls off the difficult trick of creating communicative actions down to the tiniest details of movements and gestures in a particular situation, whether the piece shows one, two or three women, or even a larger group. The more the observer moves into this group, the more they become part of these (smaller or larger) groups, as though pulled by a current, even though no sensible conclusions can be drawn about the context of the action.

A further trick by the artist consists in avoiding the anecdotal, as the intuitively coordinated actions, captured in facial expressions, do not make any obvious sense. In other words, the meaning remains open.Something happens, but what happens may shift course in one direction or the other, may dissolve. It is as if the group dynamics together with the individual figures need to be understood as a process of self-discovery within the collective setting, as a transfer of that identification of self into the collective setting.

At Home with Freud, 2001

I, Heather Allen, One, Two, Many _ or: Sigi Would Never Have dreamt Of It

Crowds of confusingly similar figures about the size of somebody’s hand and wearing everyday clothes have made themselves at home on a desk, a sofa, an armchair. Yer, wait a moment: this is no ordinary public place. This is without doubt Sigmund Freud’s studying its invasion by women rouses it from its hallowed lethargy, challenging it to respond. Certainly not warlike, rather in a spirit of enquiry, Heather Allen’s modelled clay doubles seek to explore this ultimate interior for the discovery of the unconscious, to temporarily set up camp on its site (At Home with Freud, 2001)

They take up various poses, stand about, or crouch on the desk amongst Freud’s famous collection of antiques, observe, search, marvel and reflect on the topography of the psyche. Resembling one another without being identical, these simple yet realistically modelled Sculpey figures more or less obviously share their author’s facial features, posture and hairstyle. They are naked, or casually, even sloppily, dressed in mid-blue tracksuit bottoms and black T-shirts – the impression fluctuates between that of an individual and one of a fixed type. Presumably unlike Freud’s female patients and co-inventors of psychoanalysis, their posture is as informal as their leisurewear: arms crossed under their breasts, elbows bent, legs swinging, knees drawn up under their chins. In other words: at home.

But what do these women see, crouching in front of Freud’s magnifying-glass and gazing at the glass like Narcissus athis reflection in the water? What do the soles of these naked feet learn from wandering through his autographs? And is it perhaps possible to understand more about Freud’s concept of female sexuality when eye to eye with a stone Isis?

This dialogue between precious sculpture and cheap Sculpey figures, between the unique and the reproduced could correspond to the discrepancy between the ideal and the everyday. It seems that this difference is not to be discerned without difficulty. Accordingly, Freud’s legendary couch becomes an arena in which ‘Heather’ and ‘Heather’ conduct a duel in the presence of ‘Heather’s’ 38 pairs of eyes. A number of the spectators stand or lie in the ranks of the kilim cushions, sympathetically accompanying the pair caught up in the ambiguity of a wrestling match or is it coitus, autoeroticism or aggression? Eventually, ‘Heather’ comes to lie flat out on her back on the torn leather seat of the armchair at Freud’s desk, her arms outstretched, her legs slightly open. At once as monumental and archaic as one of the idols of the Cyclades, the anthropomorphic constellation of arm and backrest appears to be bending over the toy figure. Was it not the case that for long the central role of sexuality was Freud’s most outrageous invention?

In her small-scale way, Heather Allen finds a way to translate back into a contemporary, visual form those things that Freud believed could not be diagnosed through the visual image, but which could be heard by listening to people speak, and were at best legible in the form of text, such as the relationship between the superego, the ego and id. But unlike the case with digital image technology, which make it easy to produce identical clones, Heather allen shapes her figures out of Sculpey and arranges them to form casual scenes. Whether she uses installations such as Group, 2002, or Raus!, 2002, or a photographic work (BdM Twins, 2001), both media convey the impression of a tableau vivant of a situation that, although it is everyday in the extreme, remains, at the same time, precarious. Both media allow viewers to participate in something intimate, be it the mood-related facial expression in the manner of a portrait (Heads, 2001), the conspiratorial whispering with expressions of tenderness (Chinese Whispers, 2001), or in the way we look when we look.

According to French psychoanalyst Jaques Lacan, not being able to see ourselves when we see is one of the central flaws in the subject who imagines himself to be in charge of things. This shortcoming marks both the subject’s fundamental dependency on the other and the insatiability of desire, the need to be permanently regarded and to have one’s existence confirmed by the eyes of the other. How much clearer does the infinite nature of this desire appear when replicated in the hoard of figures, whose principal function is to look. (Don’t we always cross our arms or place our hands on our hips, just so that we can see better?) Seeing ourselves reflected, whether in that little black number (Little black dress, 1998), that special pink skirt (Skirt, 2000) or naked in the gazes of other people (Naked, 2000), conveys the false impression of the ability to act autonomously. The imaginary, exposed in this, its smoothing over function, when the others present, female as they are, watch the watcher watching – by no means a relaxing experience. For gender difference is also written into the convention of the gaze. In the good old tradition of the subject, the act of seeing remains one of man’s phallic privileges and being observed characterises the position of the woman. The fact that Heather Allen’s small counterparts almost always step up and want to look tends to indicate the potential confusion arising with regard to all aspects of looking rather than their attempt to control the power of the gaze.

With Freud’s psychoanalysis as a theoretical tool, with her dextrous fingers the modelling material with its contemporary surface characteristics, and with her unerring eye for a convincing miniature screenplay. Heather Allen then also mixes in material that playfully describes the anthropological injury from a pre-modern angle – mythical material such as Eve and the Devil (Eva und der Teufel, 2002), classical material, demonstrated in the traditional pictorial genres such as landscape and (self-)portrait (Self-portraits in landscapes, 2001) or the physiognomic material, resembling Franz Xavier Messerschmidt’s 18th century “Charakterköpfen” (character heads). Here, the change of scale appears significant: on the one hand, we see her clay figures that attract attention due to their toy-like size, particularly when, with their uncanny similarity, they take the stage in crowds or groups. On the other, her photo portraits, enlarged to a size much greater that life, reveal the careful crafting of the heads as a touching form of intimacy that also references the small sculptural format.

Heather Allen has a strong understanding of metaphors for a sense of being inwardly torn, of standing outside yourself, watching yourself doing something and not being at one with yourself or wanting, in the end, to flee the confines of your nonbeing. She portrays the everyday drama wittily, using wit in the sense that it derives from the same root as wisdom.

Eva und der Teufel #3, 2001

On the Far Side of High Drama

We are moved daily by the lives and loves of celebrities, by “human interest stories” and reality TV. Personal histories are offered up by the media for general consumption, reality itself is pictured as following the patterns and cadences of the soap opera. The experience of pathos is a degraded one, a spasm of sentiment. No wonder, then, that so much of the art to today is cerebral, that it concerns itself wit mediations rather than the bare bones of lived experience.

Heather Allen has no truck with the pathos of commercial culture, or for that matter with the more rarified dramatic efforts of high art. But she is not prepared to turn her back on pathos altogether. She stops it in its tracks, deflates it, satirises it. And she suggests that when the romantic mystifications are laid to rest, another kind of pathos can emerge in their place.

(…)

There is something faintly sinister about Allen’s little figures. The multiplication of similar or identical figures often serves as a sign of doom or chaos. The proliferation of likenesses tends to occur in a nightmarish, dystopian context, witness Katherina Fritsch’s faceless clones or the Chapman brothers’ indistinguishable adolescents. Heather Allen’s little figures evoke such precedents, but avoid their grimness and theatricality – they are closer in temperament to Matisse’s identical men in black. They are not involved in identifiable events, most of them are just sitting or standing around, waiting, chatting, killing time.Their expressions are either mild or unreadable, their gestures are easy and undemonstrative, their clothes are casual. While the horror of a world of clones hovers around them und subtly conditions the viewer’s response, the figures themselves larger shun the pathos of dystopia. In fact, they actually court banality. They are toy-like in scale and colour; they have something of the mundane, domestic character, even the cuteness, of the plaything. This is their natural terrain, the no-man’s-land between pathos and banality, between the horror of dystopia and the child’s world of play.

The figures also engage and largely deflate the pathos of self-discovery. They seem to represent different moods or character traits. The artist apparently admits as much when she photographs them at the Freud Museum in London, where they gather on the famous couch and poke around on the desk. The suggestion is that they are involved in a psychological quest, that the artist has set off, with their help, on the inward journey of psychoanalysis. But look again: the figures are comically out of place in Freud’s study. They are too small, they belong to a different order of reality. With their wide-eyed expressions, they look like uncomprehending interlopers, like fairies who have strayed into an alien world of learning and introspection. They resemble the artist, but they are also Everywoman. They are at once ordinary and impenetrable, nothing about them suggests a particular trajectory, a buried personal history to be coaxed out by the analyst. They can even be seen as imagining the redundancy of psychoanalysis. After all, there is something wilfully paradoxical in the image of a group of near-identical figures on the couch: in a world of alter egos, the notion of normative or healthy behaviour is as anomalous as that of individuality.

The deflation of pathos in Allen’s work results in a peculiarly deadpan kind of humour. In her 1997 video Did she jump?, a little plasticine figure walks haltingly towards a ledge, sits for a time on it and then disappears from sight as she falls or jumps. Her back is turned to the viewer throughout; like Allen’s little self-representations, she discourages identification. The soundtrack is a short musical sequence, a couple of bars from “Bustin’ Surfboards” by the Tornadoes, which repeats over and over, constantly building to a climax, falling short of it and starting again. When the figure falls the music stops and we are left with a bright view onto the trees beyond, as if the brief narrative had been no more than a daydream.The tension between the dram and the banality of the scene, a tension that is amplified by the soundtrack, is unnerving. It is also quietly funny.

In using “Bustin’ Surfboards”, which is also on the soundtrack of Pulp Fiction, Allen is obliquely referring to Hollywood film and the reference is telling; the conventions that are subverted in her work, the conventional ways of creating pathos and surprise, are to some degree generated by Hollywood. Here, the reference only underlines the difference in purpose between Allen’s video and contemporary film. The satisfactions of empathy and psychological penetration are unavailable here. There is no dramatic denouement, no cathartic violence. The figure may or may not be committing suicide; either way, the animation is charmingly low-tech and the figure

s movements are as sweet and awkward as a child’s. In other words, the figure’s existence and actions insist on their own fictional character. That in itself undermines the drama of a hypothetical suicide. So do the dazzling light, the slow pace and repetitiveness of the soundtrack. The video imitates the ponderous final ambiguity so beloved of ‘serious’ film (American Psycho is an obvious example), but its own refusal of closure is more radical. The viewer is not left wondering just whether she jumped but how, on what terms, she could be said to have existed in the first place. And the second question seems somehow more relevant than the first.

Allen creates imaginary scenes that mimic the pathos of certain narratives, including narratives of self-discovery and loss but the pathos tends to fall flat, the discontinuities between her figures and their environments comically short-circuiting the workings of drama. But that is not to say that the scenes are unaffecting. It appears that another kind of pathos exists on the far side of high drama. That is the pathos that arises from the impenetrability of ordinary occasions, of others, of ourselves. It is the muffled pathos of events that go unseen, of thoughts and actions that defy explanation. It is a pathos without build-up or release, one that has something of the dream about stand something of the child’s imagining. What these funny, difficult, laconic pieces suggest is that pathos and banality are not opposed terms after all.